Nomenclature Ninja – Naming Alkanes

Naming organic molecules is… complicated! Or, it can sure seem that way. There’s alkynes of rules in organic nomenclature 🙂 What are the most important things to know when naming alkanes? What is a system for naming compounds? And, what is going to be on the exam?

Yes, nomenclature will be on the exam

Pretty much every organic chemistry course will start off with three topics – structure, bonding and nomenclature. And, let’s face it – it isn’t the most interesting topic! It’s like learning another language – there’s new words, prefixes, suffixes and even grammar. Bleugh! Unfortunately, it’s necessary medicine. If organic chemists don’t speak the same language, things are going to get confusing real quick. More importantly to you, as a student, it’s definitely going to be on the exam. Both explicitly, eg. “Name this compound…”, and as an important part of many other questions, eg. “What is the product formed when m-chlorobenzoyl chloride reacts with N-ethylisopropylamine?” So it pays to become a Nomenclature Ninja!

Like any other language

Just like any other language, the best way to learn to speak organic chemistry is through practice. The vocabulary is big and there are so many rules for every possible situation – it isn’t possible (and certainly not advisable!) to try to learn it all at once. Instead, you should learn the basic rules and vocabulary for alkanes and then pick up the rest as you go. And do lots of nomenclature practice!

Anatomy of an organic compound name

Before we go through a system for naming organic compounds, let’s look at the anatomy of a compound’s name:

- parent – in alkanes, the parent is the longest chain

- prefixes – these define what substituents are attached to the parent chain, and where they are located

- suffix – for alkanes, the suffix is just “ane”, for other compounds, the suffix depends on what functional groups are present

A systematic approach to naming alkanes

Let’s just ignore functional groups for now, so we don’t need to worry about any suffix except “ane”. So, here’s a systematic approach to alkane nomenclature:

- Find the parent chain – the longest chain will often be obvious. If not, make a best guess, then number each carbon atom consecutively. Then, try other possibilities until you’re sure that you have the longest chain. Tie-breaker: if two chains are equal in length, choose the one with more substituents.

- Find and name all the substituents – alkyl substituents will normally end in “yl”, eg. methyl, ethyl, propyl.

- Number the parent chain – start from the end that makes the first substituent as low a number as possible. Note: this may be the opposite direction to how you numbered when determining the longest chain! Tie-breaker: if the first substituent in both directions is in the same position, look for the second substituent to have a lower number, as so on.

- Assign a “locant” to each substituent – the carbon number where the substituent is attached is called a locant. Write down the locant for each substituent.

- Group together identical substituents – if there are multiple identical substituents, they get grouped with their own prefix to say how many there are, eg. di (2), tri (3), tetra (4).

- Write out the substituents alphabetically – ignore numbers (locants) and the di/tri/tetra prefixes when alphabetizing. Separate consecutive locants with commas, eg. “3,4-diethyl”. Separate locants from substituents with hyphens, eg. “3,4-diethyl-5-methyl”.

- Finally – don’t separate the parent name from the final prefix, eg. “3,4-diethyl-5-methylnonane”. It might look strange, but we really do just squish them together like that!

But, what parent alkanes and substituents do I need to know?

It depends on your professor and your course, but most instructors would want you to know the names for all the unbranched alkanes from 1 to 12 carbons. I don’t think this is a sticking point for many students, so I won’t spend much time on it, but if you’re unsure, expand the table below.

In my experience, the most common mistake is getting propane / propyl (3 carbons) confused with pentane / pentyl (5 carbons). If it helps, think of a propeller, like on a wind turbine. I know propellers come in all different shapes and sizes, but to my mind, three blades are the most common. Propeller – 3 blades, propane – 3 carbons!

Here’s an example of naming an alkane using these rules, and exposing a common trick Professors will employ in exam questions on nomenclature of alkanes:

Branching out – what about more complex substituents?

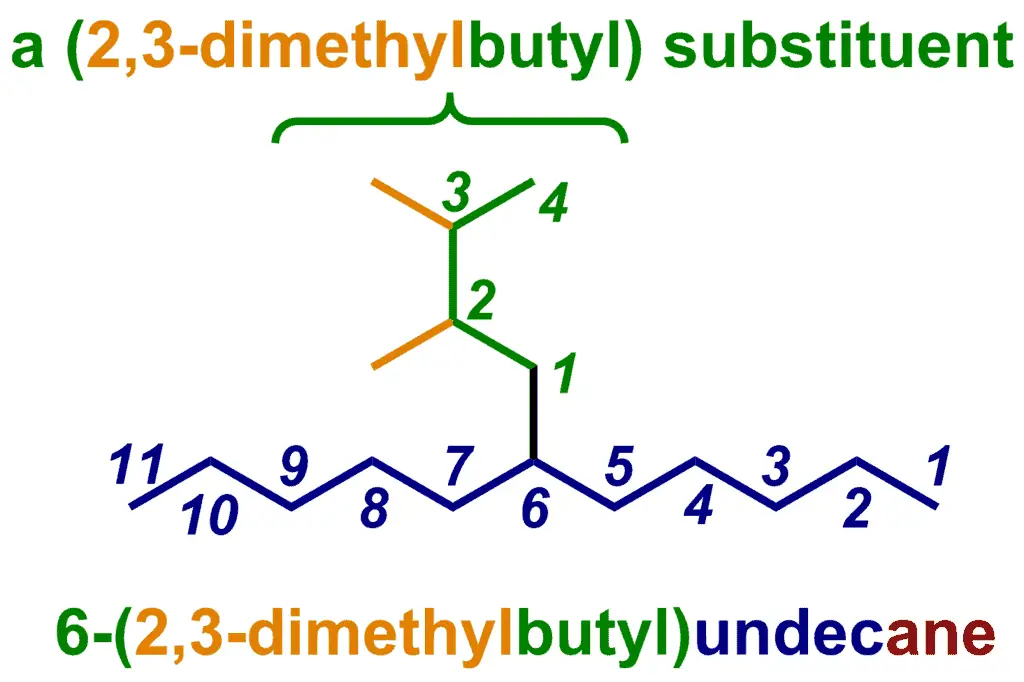

Things get ‘interesting’ when the substituents get more complex. If the alkyl group is connected at the end of the longest chain, we just assume that is the “1-” position, find the substituents along the chain, then number and name them.

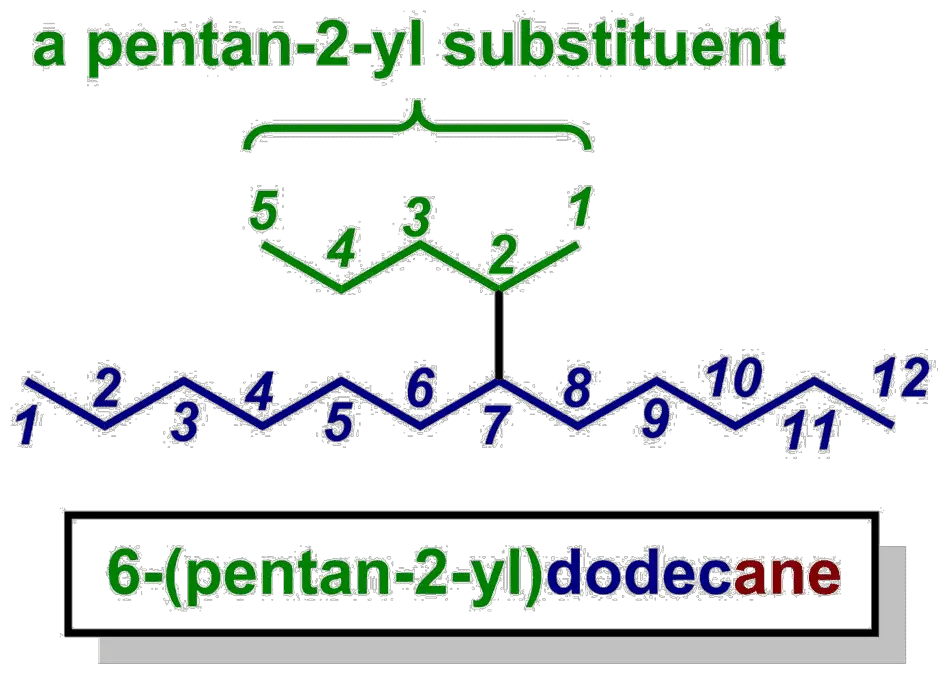

What do we do if the substituent is an alkyl chain, but it’s not connected to the parent at its own terminus? Well, the IUPAC system uses locants again. If the substituent is a simple, unbranched chain, that just happens to be attached at a non-terminal carbon, then we number the chain from the end closest to the point of attachment and then use the attachment point as a prefix for that substituent.

Now that the substituent is a bit more complicated, notice how we’ve put the substituent name in brackets after the locant (“6-“) that tells us where it is located on the parent chain.

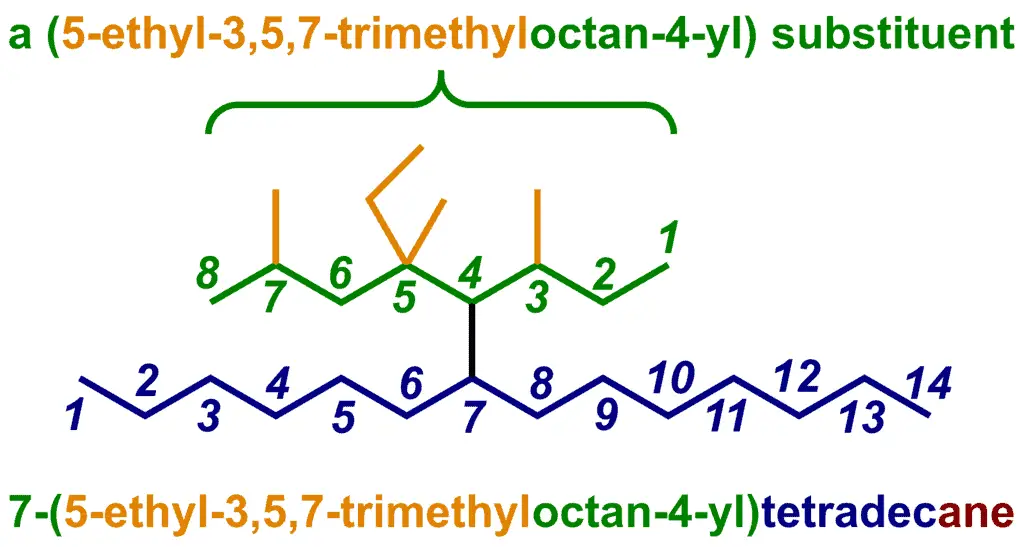

For a branched-chain substituent, find the longest chain, then number this so that the attachment point to the parent chain has the lowest possible number. Then, identify the substituents and give them numbers. Hand out your di’s and tri’s, put it all in parentheses, and voila, you’re done! Here’s an example:

It turns out that some of these complex, branched chain examples are quite contrived. You might come across this in practice questions, or maybe even an exam, but it would only be to test understanding of the nomenclature rules. What are really important are a small set of branched alkyl groups that extremely common. So common, in fact, that they have their own “trivial”, or non-standard IUPAC names.

Common branched-chain alkyl substituents

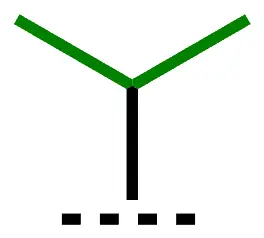

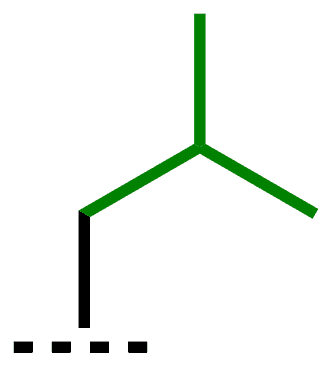

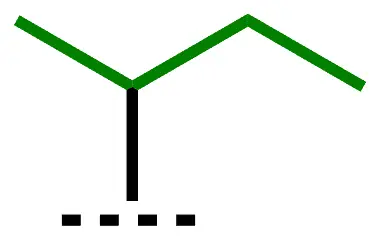

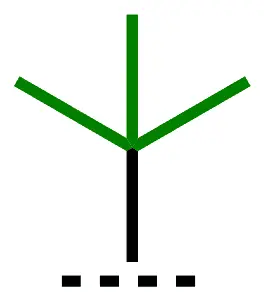

Let’s cut to the chase. Below are the most common branched-chain alkyl substituents that you’re going to need to know. Do you know the common (trivial) name for each one?

…and their abbreviations

These small branched-chain alkyl groups are so common that they are often shown using abbreviations, and you really need to learn these too! And don’t forget that the unbranched butyl group is normally called n-butyl (n-Bu), to distinguish it from the branched-chain homologues.

| Structure | Abbreviations | Common name | IUPAC name |

|---|---|---|---|

| i-Pr | isopropyl | 1-methylethyl |

| i-Bu | isobutyl | 2-methylpropyl |

| sec-Bu, s-Bu | sec-butyl | butan-2-yl |

| tert-Bu, t-Bu | tert-butyl | 1,1-dimethylethyl |

You know the English spelling rule – ‘i’ before ‘e’, except after ‘c’… except, for the HUNDREDS of exceptions! (seriously, this rule is very flaky…) Well, the language of organic chemistry is also guilty! You know how we said earlier that prefixes like “di”, “tri” and “tetra” don’t count when alphabetizing? Well, neither do the prefixes in front of common substituents, like tert– and sec-. Except,.. “iso” isn’t counted as a prefix! So, in terms of alphabetical order, “isobutyl” starts with an “i”, whereas “sec-butyl” and “tert-butyl” both start with the letter “b”. Don’t ask me why – I have no idea! But, we’re stuck with it!

Here’s a final example, this time including substituents with common names:

Practice – the way of the nomenclature ninja

Well, that’s the basic rules for alkanes. The rest is better to pick up along the way, as different types of structures come up. And the best way to become a nomenclature ninja is to practice – check out my next post to practice alkane nomenclature with Alkane Spaghetti!

Very nice sir